mirror of

https://github.com/huggingface/diffusers.git

synced 2026-01-29 07:22:12 +03:00

* add stable diffusion jax guide --------- Co-authored-by: Patrick von Platen <patrick.v.platen@gmail.com>

250 lines

10 KiB

Plaintext

250 lines

10 KiB

Plaintext

# 🧨 Stable Diffusion in JAX / Flax !

|

||

|

||

[[open-in-colab]]

|

||

|

||

🤗 Hugging Face [Diffusers](https://github.com/huggingface/diffusers) supports Flax since version `0.5.1`! This allows for super fast inference on Google TPUs, such as those available in Colab, Kaggle or Google Cloud Platform.

|

||

|

||

This notebook shows how to run inference using JAX / Flax. If you want more details about how Stable Diffusion works or want to run it in GPU, please refer to [this notebook](https://huggingface.co/docs/diffusers/stable_diffusion).

|

||

|

||

First, make sure you are using a TPU backend. If you are running this notebook in Colab, select `Runtime` in the menu above, then select the option "Change runtime type" and then select `TPU` under the `Hardware accelerator` setting.

|

||

|

||

Note that JAX is not exclusive to TPUs, but it shines on that hardware because each TPU server has 8 TPU accelerators working in parallel.

|

||

|

||

## Setup

|

||

|

||

First make sure diffusers is installed.

|

||

|

||

```bash

|

||

!pip install jax==0.3.25 jaxlib==0.3.25 flax transformers ftfy

|

||

!pip install diffusers

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

import jax.tools.colab_tpu

|

||

|

||

jax.tools.colab_tpu.setup_tpu()

|

||

import jax

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

num_devices = jax.device_count()

|

||

device_type = jax.devices()[0].device_kind

|

||

|

||

print(f"Found {num_devices} JAX devices of type {device_type}.")

|

||

assert (

|

||

"TPU" in device_type

|

||

), "Available device is not a TPU, please select TPU from Edit > Notebook settings > Hardware accelerator"

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python out

|

||

Found 8 JAX devices of type Cloud TPU.

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Then we import all the dependencies.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

import numpy as np

|

||

import jax

|

||

import jax.numpy as jnp

|

||

|

||

from pathlib import Path

|

||

from jax import pmap

|

||

from flax.jax_utils import replicate

|

||

from flax.training.common_utils import shard

|

||

from PIL import Image

|

||

|

||

from huggingface_hub import notebook_login

|

||

from diffusers import FlaxStableDiffusionPipeline

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

## Model Loading

|

||

|

||

TPU devices support `bfloat16`, an efficient half-float type. We'll use it for our tests, but you can also use `float32` to use full precision instead.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

dtype = jnp.bfloat16

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Flax is a functional framework, so models are stateless and parameters are stored outside them. Loading the pre-trained Flax pipeline will return both the pipeline itself and the model weights (or parameters). We are using a `bf16` version of the weights, which leads to type warnings that you can safely ignore.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

pipeline, params = FlaxStableDiffusionPipeline.from_pretrained(

|

||

"CompVis/stable-diffusion-v1-4",

|

||

revision="bf16",

|

||

dtype=dtype,

|

||

)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

## Inference

|

||

|

||

Since TPUs usually have 8 devices working in parallel, we'll replicate our prompt as many times as devices we have. Then we'll perform inference on the 8 devices at once, each responsible for generating one image. Thus, we'll get 8 images in the same amount of time it takes for one chip to generate a single one.

|

||

|

||

After replicating the prompt, we obtain the tokenized text ids by invoking the `prepare_inputs` function of the pipeline. The length of the tokenized text is set to 77 tokens, as required by the configuration of the underlying CLIP Text model.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

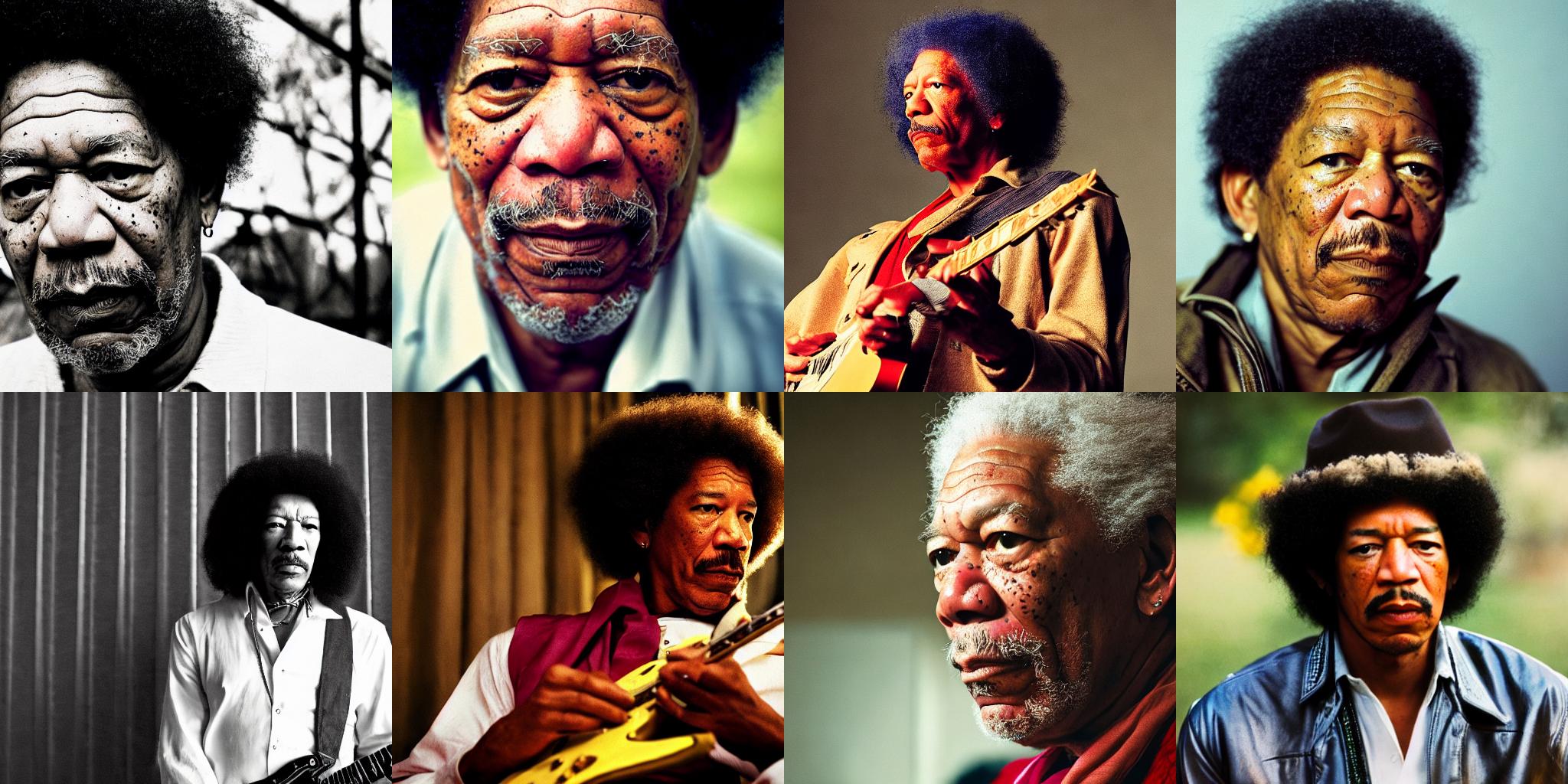

prompt = "A cinematic film still of Morgan Freeman starring as Jimi Hendrix, portrait, 40mm lens, shallow depth of field, close up, split lighting, cinematic"

|

||

prompt = [prompt] * jax.device_count()

|

||

prompt_ids = pipeline.prepare_inputs(prompt)

|

||

prompt_ids.shape

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python out

|

||

(8, 77)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Replication and parallelization

|

||

|

||

Model parameters and inputs have to be replicated across the 8 parallel devices we have. The parameters dictionary is replicated using `flax.jax_utils.replicate`, which traverses the dictionary and changes the shape of the weights so they are repeated 8 times. Arrays are replicated using `shard`.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

p_params = replicate(params)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

prompt_ids = shard(prompt_ids)

|

||

prompt_ids.shape

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python out

|

||

(8, 1, 77)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

That shape means that each one of the `8` devices will receive as an input a `jnp` array with shape `(1, 77)`. `1` is therefore the batch size per device. In TPUs with sufficient memory, it could be larger than `1` if we wanted to generate multiple images (per chip) at once.

|

||

|

||

We are almost ready to generate images! We just need to create a random number generator to pass to the generation function. This is the standard procedure in Flax, which is very serious and opinionated about random numbers – all functions that deal with random numbers are expected to receive a generator. This ensures reproducibility, even when we are training across multiple distributed devices.

|

||

|

||

The helper function below uses a seed to initialize a random number generator. As long as we use the same seed, we'll get the exact same results. Feel free to use different seeds when exploring results later in the notebook.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

def create_key(seed=0):

|

||

return jax.random.PRNGKey(seed)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

We obtain a rng and then "split" it 8 times so each device receives a different generator. Therefore, each device will create a different image, and the full process is reproducible.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

rng = create_key(0)

|

||

rng = jax.random.split(rng, jax.device_count())

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

JAX code can be compiled to an efficient representation that runs very fast. However, we need to ensure that all inputs have the same shape in subsequent calls; otherwise, JAX will have to recompile the code, and we wouldn't be able to take advantage of the optimized speed.

|

||

|

||

The Flax pipeline can compile the code for us if we pass `jit = True` as an argument. It will also ensure that the model runs in parallel in the 8 available devices.

|

||

|

||

The first time we run the following cell it will take a long time to compile, but subequent calls (even with different inputs) will be much faster. For example, it took more than a minute to compile in a TPU v2-8 when I tested, but then it takes about **`7s`** for future inference runs.

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

%%time

|

||

images = pipeline(prompt_ids, p_params, rng, jit=True)[0]

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python out

|

||

CPU times: user 56.2 s, sys: 42.5 s, total: 1min 38s

|

||

Wall time: 1min 29s

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The returned array has shape `(8, 1, 512, 512, 3)`. We reshape it to get rid of the second dimension and obtain 8 images of `512 × 512 × 3` and then convert them to PIL.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

images = images.reshape((images.shape[0] * images.shape[1],) + images.shape[-3:])

|

||

images = pipeline.numpy_to_pil(images)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Visualization

|

||

|

||

Let's create a helper function to display images in a grid.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

def image_grid(imgs, rows, cols):

|

||

w, h = imgs[0].size

|

||

grid = Image.new("RGB", size=(cols * w, rows * h))

|

||

for i, img in enumerate(imgs):

|

||

grid.paste(img, box=(i % cols * w, i // cols * h))

|

||

return grid

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

image_grid(images, 2, 4)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

## Using different prompts

|

||

|

||

We don't have to replicate the _same_ prompt in all the devices. We can do whatever we want: generate 2 prompts 4 times each, or even generate 8 different prompts at once. Let's do that!

|

||

|

||

First, we'll refactor the input preparation code into a handy function:

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

prompts = [

|

||

"Labrador in the style of Hokusai",

|

||

"Painting of a squirrel skating in New York",

|

||

"HAL-9000 in the style of Van Gogh",

|

||

"Times Square under water, with fish and a dolphin swimming around",

|

||

"Ancient Roman fresco showing a man working on his laptop",

|

||

"Close-up photograph of young black woman against urban background, high quality, bokeh",

|

||

"Armchair in the shape of an avocado",

|

||

"Clown astronaut in space, with Earth in the background",

|

||

]

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

prompt_ids = pipeline.prepare_inputs(prompts)

|

||

prompt_ids = shard(prompt_ids)

|

||

|

||

images = pipeline(prompt_ids, p_params, rng, jit=True).images

|

||

images = images.reshape((images.shape[0] * images.shape[1],) + images.shape[-3:])

|

||

images = pipeline.numpy_to_pil(images)

|

||

|

||

image_grid(images, 2, 4)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

## How does parallelization work?

|

||

|

||

We said before that the `diffusers` Flax pipeline automatically compiles the model and runs it in parallel on all available devices. We'll now briefly look inside that process to show how it works.

|

||

|

||

JAX parallelization can be done in multiple ways. The easiest one revolves around using the `jax.pmap` function to achieve single-program, multiple-data (SPMD) parallelization. It means we'll run several copies of the same code, each on different data inputs. More sophisticated approaches are possible, we invite you to go over the [JAX documentation](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/index.html) and the [`pjit` pages](https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/jax-101/08-pjit.html?highlight=pjit) to explore this topic if you are interested!

|

||

|

||

`jax.pmap` does two things for us:

|

||

- Compiles (or `jit`s) the code, as if we had invoked `jax.jit()`. This does not happen when we call `pmap`, but the first time the pmapped function is invoked.

|

||

- Ensures the compiled code runs in parallel in all the available devices.

|

||

|

||

To show how it works we `pmap` the `_generate` method of the pipeline, which is the private method that runs generates images. Please, note that this method may be renamed or removed in future releases of `diffusers`.

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

p_generate = pmap(pipeline._generate)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

After we use `pmap`, the prepared function `p_generate` will conceptually do the following:

|

||

* Invoke a copy of the underlying function `pipeline._generate` in each device.

|

||

* Send each device a different portion of the input arguments. That's what sharding is used for. In our case, `prompt_ids` has shape `(8, 1, 77, 768)`. This array will be split in `8` and each copy of `_generate` will receive an input with shape `(1, 77, 768)`.

|

||

|

||

We can code `_generate` completely ignoring the fact that it will be invoked in parallel. We just care about our batch size (`1` in this example) and the dimensions that make sense for our code, and don't have to change anything to make it work in parallel.

|

||

|

||

The same way as when we used the pipeline call, the first time we run the following cell it will take a while, but then it will be much faster.

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

%%time

|

||

images = p_generate(prompt_ids, p_params, rng)

|

||

images = images.block_until_ready()

|

||

images.shape

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python out

|

||

CPU times: user 1min 15s, sys: 18.2 s, total: 1min 34s

|

||

Wall time: 1min 15s

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python

|

||

images.shape

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```python out

|

||

(8, 1, 512, 512, 3)

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

We use `block_until_ready()` to correctly measure inference time, because JAX uses asynchronous dispatch and returns control to the Python loop as soon as it can. You don't need to use that in your code; blocking will occur automatically when you want to use the result of a computation that has not yet been materialized. |